Sermons by the Ministers who Serve

Pride Sermon Rev John Rex

A UU Christmas Sermon Rev. John Rex

It's All in the Assumptions Rev. Richard Hood

Heroes? Yesterdays and Todays Rev. Richard Hood

Rationale for UU Ministry Rev. Donald Reidell

So Whats the Big Deal Rev. Richard Hood

The You in UU to Me Susan Dodge Peters

Continuing Revelation (Outline) Rev. Donald Reidell

A Masterpiece in Our Midst Rev. Richard Hood

Sermon on Blaise Pascal Rev. Donald Reidell

The Sermon on the Mount Rev. Donald Reidell

Spirit Rev. Donald Reidell

PRIDE

SERMON

The

June 10, 2007

A

UU CHRISTMAS SERMON

The

December 10, 2006

I put up my Christmas tree this past week. I bought this artificial

tree when I was ministering to a congregation in

Notice

that I am tentative in trying to say all this as I consider my spiritual life a

work in progress, a journey, and the older I get, the more I realize how much I

don't know and how important it is to listen to what others have to say and to

be authentic and true to myself. One thing that I have become aware of as years

go by is the extent to which I am culturally an Episcopalian. I was

raised in a church that had wonderful massive bells that we young people rang by

pulling ropes which we could ride high in the air. We had a terrific

organ and choir that gave me a lifelong love of classical and choral music.

We had a liturgy that exposed me weekly to the finest cadences of the English

language. It was a place of great beauty and love, and Christmas was

for me a

I

remember one UU children's service where the central event was the arrival of

Santa Claus--in fact a miniature sleigh had been rigged to fly on a wire over

the heads of the congregation. I have seen any number of pageants

with our children dressed in improvised costumes, the smallest being angels,

reenacting events surrounding the biblical birth of Jesus. At least

one UU church in the area has a yearly tradition of interpretive dance on

Christmas Eve. Somehow, though, we UU's always manage a disclaimer: the

Bible stories of the birth of Jesus are not history; these are ancient myths

created according to ancient traditions. I have said it myself in Christmas

sermons, how common accounts were of miraculous virgin births of important

leaders, how we don't know when or where Jesus was born, but the time of the

winter solstice was a holiday long before early Christians made it their own,

choosing

It

helps to know that something like eighty percent of our members are not

birthright UU's, that we come from many traditions including atheist, agnostic,

Jewish, and a whole range of Christianities, from conservative to liberal.

One "New UU" class I led in a church I served had six members, all

ex-Catholics. Those folks carried in them a lifelong "catholic"

perspective, in a sense giving definition to their newly embraced Unitarian

Universalism. For them, as for many of our new members, Unitarian

Universalism is defined by what they no longer believe or accept. I suggest that

how we understand our religion can only be understood in the perspective of what

we learned as children. I remember taking a second grade UU Sunday

school class to visit the "church across the street," which happened

to be Baptist, and having one of our children, whose parents were Jewish UU's,

blurt out that of course we were all Jewish. I think we carry those early

teachings and experiences with us all our lives, and we understand what comes

later in terms of what we learned earlier.

As I presented a month ago, there are stages in our growing faith: in moving on, we reject what we were taught as untrue, and we may have some anger or other emotional reaction towards the teachings we received that we now perceive as wrong. There is a lot of that in UU churches--often coming out as rejection of Biblical or traditional teachings. Yes, some people who have been hurt by religion come to us, seeking community and affirmation, but wanting nothing to do with church or worship or sermons or the Bible or ministers... or, you name it. There are critical pitfalls in all this:

1)

that we UU's begin to think that we have the answers while others don't, a kind

of arrogance,

2)

that we UU's lose our connection with our own heritage in Western biblical

culture, and

3)

that we UU's find ourselves cut off from faith communities around us--the butt

of Garrison Keillor's jokes as the oddball church, the one that doesn't fit in.

I

might add that I am a big fan of Garrison Keillor, and I enjoyed his live

appearance in

So

there is the dilemma for some of us: how do we best deal with our overwhelming

cultural holiday of Christmas, when we don't quite fit into that culture?

For a start, let's go back to what I have called the "pitfalls." Number

one, thinking that we know something that others don't know. Let's

get over that. Most of our valued purposes and principals are valued

in various ways by other religions. When we say we "affirm and

promote the inherent worth and dignity of every person," and think that is

different from what others teach, we are hugely mistaken. The Golden

Rule--do unto others as you would have them do unto you--is a part of all world

religions. Affirming worth and dignity is a large part of many

religions, though, granted, in different ways. Each religion sets

limits on who and what is not OK. We do that too. See what

happens when a sexual predator or child molester wants to join a UU

congregation. Not everyone is welcome equally.

Many

of our American Christian churches draw wisdom from the same scholarship

that we UU's know. They know that the biblical Christmas stories

are not literally true, are myths. They celebrate them because they

are such wonderful, powerful, meaningful myths, so firmly imbedded in our

culture that we cannot live without them. The issue is not whether

Jesus really was born in such a place at such a time or that kings or wise men

or shepherds came to a manger. The issue is that a man with

extraordinary presence and ideas was born long ago, and we wish to celebrate

his birth, the symbol of new life and hope. We celebrate the end of

darkness, the winter solstice, the coming of the light. For me, the

Santa Claus myth, even understood as it may be as at a representation of

warmth and love all around, falls far short of the ancient birth in

I

think too often, in rejecting mainstream beliefs, Unitarian Universalists ignore

their own heritage. We forget that we come out of a profound and

meaningful history, and that most of our religious ancestors were devout

Christians. Think of Frances David and King John Sigismund--the first

and only Unitarian king-- John Murray, Hosea Ballou, Olympia Brown--the list

goes on and on of people we honor as our founders, all Christian. Those who

ended up being called and then calling themselves Unitarians questioned the

nature of the trinity, and those who ended up being called and calling

themselves Universalists said that all would be saved, but they did so within a

firm biblical context. Yes, we have grown, evolved, become different from what

we were. Our churches that are built today do not feature stained

glass windows with Jesus, as does this church and the First Universalist Church

of Rochester where I was an intern minister. We now prefer banners

and windows representing a variety of faith traditions, with multiple symbols

all around. We have chosen a new symbol of our own, the flaming chalice, first

designed for the Unitarian Service Committee in the Nazi era, and officially

brought into our churches in the 1970's.

But,

I think it is a mistake for us to forget our origins. I have heard many times,

from enthusiastic, liberated, new UU's, that they love this new found religion

because they can "believe anything they want." I admit that

I am uncomfortable when I hear those words spoken in that way. My

religion, my Unitarian Universalism, is not a matter of what I believe. It

is a matter of what I do. Unfortunately, for some people, believing

whatever they want translates into doing whatever they want, and I have known

people who go to our churches--not this church, of course--because there they

can be less than kind or considerate or compassionate with others, while they

expect others to be kind or considerate or compassionate with them. It

happens. Why is that? An anecdote from George Will's 12/8/06 column

in the Buffalo News may help, and I quote, speaking of

"In

June 2004, at the time the Coalition Provisional Authority was to transfer

sovereignty to what it thought would be an Iraqui government, Americans were

toiling to finish their work of occupation. The Washington Post's

Rajiv Chandrasekaran had a driver who, like other Iraquis, had obeyed the laws

under Saddam's police state but now began disregarding all traffic laws. 'When

I asked him what he was doing, he turned to me, smiled, and said, 'Mr. Rajiv,

democracy is wonderful. Now we can do whatever we want.'"

It's

human nature--what happens when we discover new and previously unknown

freedom... For me, learning of our religious ancestors, the struggles they went

through to advance freedom, reason, and tolerance in their churches, is very

important. We have a long and profound history, and I think knowing

of it should be a part of our identity. If we lack such grounding, perhaps we

deserve Garrison Keillor's teasing more than we realize.

Historically,

Unitarians and Universalists celebrated Christmas along with other Christian

religions. In fact there are wonderful stories about how our members

wrote some of our favorite hymns and created some of our most special Christmas

stories. Unitarian poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote the words to

"I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day," and Unitarian minister Edmund

Hamilton Sears wrote "It Came Upon the Midnight Clear." James Pierpont,

music director of the

I

regret that Unitarian Universalist congregations seem so often to be cut

off from the churches around them. This being

Pullman Memorial Universalist Church

January 30, 2005

Rev. Richard E. Hood

"It's All in the Assumptions "

We Universalists have a founder, largely forgotten. I have preached about him and his unique story a few times. I won't give you those details today. Suffice it to say that our founder's name is John Murray. He arrived from England on 1770. Through a variety of strange circumstances he preached his first sermon, the first Universalist sermon in America, on the day after he arrived in a small meeting house on the Jersey shore.

By all accounts Murray was a scholarly man, and a gifted minister. He did suffer from very poor eyesight, but nevertheless served with distinction as a chaplain in the Revolutionary army and later as a minister in both Gloucester and Boston, Massachusetts.

You wouldn't recognize today what John Murray called Universalism. Murray was, in many ways, what we might consider today an orthodox Christian. He believed in the Bible as the true revelation of God. He believed in the Trinity, miracles, and the necessity of baptism. I'm not sure if he ever wrote down what he thought about the Virgin Birth, but he likely thought it was ok. I also gather from reading accounts that he could be somewhat intolerant of others who did not hold his views.

But Murray made an important and necessary step in the evolution of our faith. He believed that it was the responsibility of each person to read and interpret scripture. And he believed most people got it all wrong. Murray heard the popular theology of the time, especially about the issue of salvation. Theologians has pretty much embraced a doctrine called the salvation of the elect. Certain souls, it was believed, were preordained at creation to go to heaven. Conversely, most souls were preordained for damnation. There was no way around this arbitrary allocation of souls to their final resting places. Some were "elected" for heaven; most were not.

Murray found in his reading of the Bible a radically different interpretation. He believed that scripture said that everyone, that is ALL souls, will eventually go to heaven. Many might suffer in hell for a while to somehow pay for a life of evil, but that, in the end, God will be Loving and Merciful.

Murray never had any intention of founding a separate church or denomination. He thought that if he could articulate the correct (in his view) interpretation of scripture that all of Christianity, or at least all of Protestantism, would accommodate this new belief, commonly referred to as Universal Salvation.

Was Murray wrong! He met with firm resistance on both sides of the Atlantic, and ended up in a separatist church which even today remains outside mainstream Christianity and forbidden from membership in the World Council of Churches.

Today Murray is almost forgotten. His Universalist movement took his methodology of individually interpreting scripture and widened it to mean all religious statements and values. The power of the individual, once unleashed, could never be bottled up again in a church of dogma and creed.

Today the typical Unitarian Universalist would be light years away from John Murray's ideas, or so in would seem at first glance.

I have a friend whose favorite expression is this: "It's all in the details." I've never quite figured out what he means by that, but I love the simplicity of the syntax. I'd like to steal from him this morning and give you my version of a simple sentence: "It's all in the assumptions."

What I mean is this: We may think, at first glance, that we have little if anything in common with our Universalist Christian roots of over 200 years ago. We've outgrown them, or so we might think. Many of us have found, in this very church, refuge from the very kind of orthodoxy that John Murray represented. I think the view that we have outgrown the past is wrong. Oh yes, our theology has changed. But, ah ha, it's all in the assumptions.

A deeper examination of John Murray and early Christian Universalism reveals that the sometime radical assumptions made by those early pioneers are very much alive and part of our belief system today. Murray continues to influence us, even from his grave.

What are those assumptions? There are three, I believe. Let me tell you a little bit about each one.

Murray believed God was a loving God, in contrast to the cruel and judgmental God of the Calvinists. Today, whatever our practices about how we refer to the deity, we all assume that the order of the universe is somehow one that is nurturing and enabling. God is love was the slogan back then. Today we have no such easy words, but we share an assumption that somehow the world matters, that there is a power beyond our comprehension and outside of ourselves, and that somehow that ground of our being is good, or at least neutral. We are not put on this earth to be eternally punished. In spite of all the evil and pain, we somehow assume that there is goodness and we ought to pursue it. Murray's assumptions live on.

John Murray also made assumptions about the nature of humankind that differed markedly from those of his day. We are not merely doomed sinners. Somehow we have a purpose and a calling, and that is somehow related not just to God, but to how we treat one another.

Christianity during Murray's time, as it is somewhat today, focused on matters of salvation and acceptance. Save the world! Believe in Jesus! Be a mission to the message! The ideas of good works, social responsibility, and the Golden rule were somehow lost, or at least dimmed.

Murray reclaimed from the gospels that concept that we have responsibility for the world in which we live and all of its inhabitants. We are not merely on earth as some sort waiting room waiting for the eternity train to arrive. The here and now is important, and we have duties that come with our very existence.

Today we have in our Seven Principles these words: " [We] affirm and promote the inherent worth and dignity of every person; Justice, equity, and compassion in human relations." John Murray would be very comfortable with those words, they were part of his assumptions.

Finally, Murray made new and radical assumptions about that place of the individual in determining religious truth. Up until this time there were two main avenues of religious insight: the church and the Bible. Oh yes, both had its individual interpreters, but the pope and the Bible still reigned supreme in the world of Christianity. Murray began to walk down a third avenue as part of the late Reformation. Individuals can look at the Bible and draw their own conclusions. Individual experience and needs, common sense, and personal insight all play a part in determining our beliefs. "You may possess a small light," wrote Murray, but "use it to bring more light and understanding to the hearts and minds of men and women."

By no means was he a radical in this matter. Scripture was still paramount. But Murray opened doors that others walked through. His assumption of individual insight is something we would likely all agree with today.

John Murray and his old Christian Universalism live on today. His name may be dimmed, his assumptions are very much still with us. And, after all, "it's all in the assumptions."

Albion

January 11, 2004

Heroes?

Yesterdays and Todays

This morning I want to introduce you to two heroes- people who, unusually

under adversity, changed the way we live and whose lives continue to influence

us today.

Well come back to talk more about the concept of hero a

little later.

First, an

introduction.

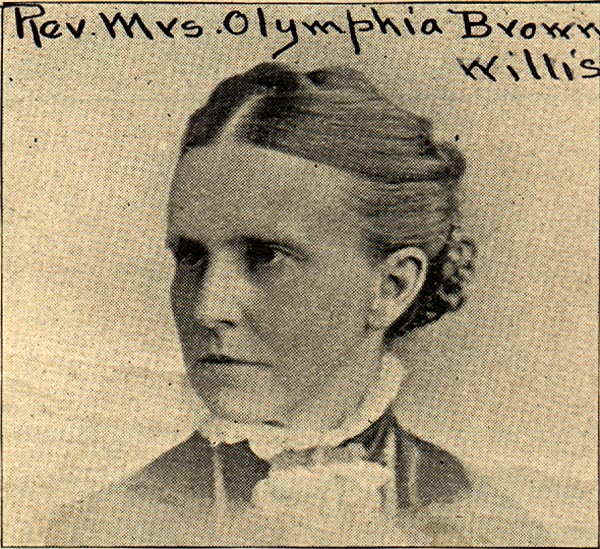

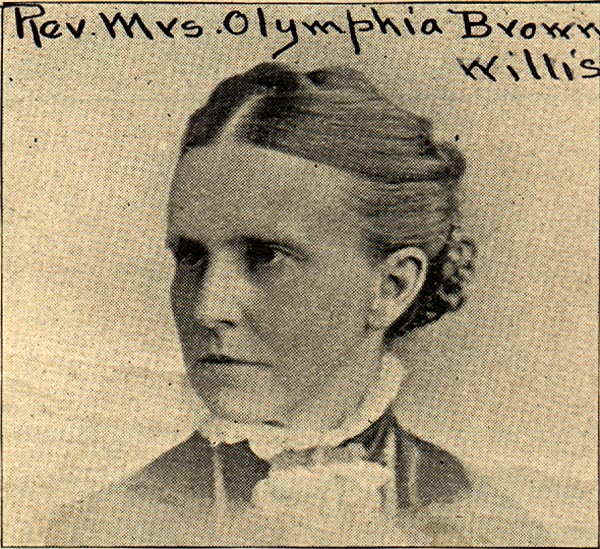

Id like you to meet a woman named Olympia Brown.

Olympia was born on January 5

th

(happy belated birthday!),

1835 in the rugged Michigan frontier.

Her

parents were early Universalists and deeply believed in a strong education for

all their four children, regardless of sex.

Olympia took advantage of a rare opportunity and actually graduated from

Antioch College in 1860, at the age 25.

During

that time her emerging social conscience began.

She was active in a movement to change the law so that women

could own property.

While a student

at Antioch, Olympia decided to enter the ministry.

Women just didnt do that sort of thing back then.

After graduation, she wrote all the prominent theological schools. Most

of them turned her down flat.

Women

were not allowed.

Only one school

expressed even the slightest bit of encouragement,

the Universalist school at Canton, NY.

She grabbed the chance and moved to northern NY.

It was not an- easy time for Olympia, although she felt she was treated

fairly by the school.

She did gain

some parish experience and did well in her studies.

The president of the school spoke openly that he didnt think women

belonged in the ministry.

And,

interesting, her greatest opposition came from wives of faculty members. The

wife of the president warned that soon women will be flocking to the

ministry with disastrous results.

Well,

she was half right anyway.

She made it through Canton (now St. Lawrence).

But she faced another hurdle- she had to convince the Northern

Universalist Association to ordain her.

Olympias

professors were unanimously against ordination.

Many warned her

that even if

she were ordained no church would ever call her.

Olympia addressed the council herself. She pointed out that she had met

all the requirements, educational and moral, for ordination.

There was nothing in Universalist bylaws which forbade female ordination.

She wanted to be judged solely on her merits.

In a surprising decision, those northern NY Universalists narrowly agreed

to ordination.

Olympia Brown became the first woman in the United States to be ordained

by a legal body of a national denomination.

Olympia Brown was almost immediately called to a struggling Universalist

parish in Weymouth, Massachusetts.

She

served several other parishes with distinction.

At the same time, her career was marked with strong support of the still

unpopular womens rights movement, especially in the area of suffrage.

She did marry, but kept her family last name (a precursor of what took

well over 100 years to be acceptable).

In 1920, Olympia Brown had

the

honor that few of the original suffrage movement lived to experience.

She voted in her first presidential election. She was 85 years old.

Always an idealist, she spoke of the experiences of her life and her

service to Universalism by saying:

The grandest thing has been

opening the doors to the

Women of America, giving liberty to twenty-seven

million women

a new and larger life and a higher ideal.

Now a second introduction, and a personal note.

I grew up in the First Parish in Waltham, Massachusetts,

Universalist-Unitarian.

The

womans group has a strange name that for years I didnt understand. They

called themselves The Phoebe Hanaford Society in honor of one of the

churchs ministers.

Let me introduce Phoebe to you.

Phoebe Hanaford did not share in any way a childhood similar to Olympia

Brown.

She was born in 1829 on

Nantucket Island, off of Cape Cod in Massachusetts.

Her father, not surprisingly, was a ship owner. The family were Quakers.

She was an energetic child. She wrote at a young age, and actually

published her first poem, at the age of 13. She married Dr. Joseph Hanaford at

the age of 20 and dutifully converted to his Baptist faith.

They had two children, but by 1857 the marriage had started to

deteriorate. Economic troubles and family moves did not help the situation.

Phoebes inquiring mind and fighting spirit remained constant. She

published a total of 14 books, adding needed money to the family coffers. She

was active in the anti-slavery movement.

She

also kept reading about theology.

Eventually

she came to reject her Baptist church and became a Universalist in 1864.

It appears she was invited in Nantucket to give a talk on her new

Universalist faith.

Something

clicked.

Phoebe decided to become a

minister.

Olympia Brown and Phoebe Hanaford met through their associations in the

antislavery and temperance movement.

Brown

invited Phoebe to preach at her church in Canton, Massachusetts.

Brown was so impressed with Hanaford that she urged her to enter the

ministry, even though she lacked the usual education. Phoebe Hanaford petitioned

the high-sounding Committee of Fellowship, Ordination, and Disciplines of the

Massachusetts Universalist Convention.

The

committee gave her a license, albeit at first only for a year.

She was the second woman Universalist minister. She also

became the first woman minister in her state.

Evidently, Phoebe had tremendous talent both in writing and in the

pulpit.

She was quickly called to

the Universalist Society of Hingham in 1866.

Another barrier had been overcome.

In

1869 Hanaford needed more income. She stayed in Hingham and also accepted a half

time position in Waltham, Massachusetts, my hometown.

She received $1,000 per year. I must admit that history records that a

least one man left the Waltham church in disgust over a woman minister saying

that if I had a hen that crowed [like that], Id cut its head off.

Hanaford went on to several other churches in her career. She separated

from her husband, although they never formally divorced.

In the course of her career she had numerous firsts in her life, as the

first woman to perform many traditional male clerical roles.

To her death she was a strong advocate for womans rights, the cause of

peace, and the temperance movement.

She spent the final days of her life with her niece in Rochester. She

died at the ripe old age of 92 and is buried in Orleans, NY, a village northeast

of Canandaigua.

The road pioneered by Brown and Hanaford has become more well-traveled,

both within the Universalist movement and within Protestantism in general.

In the 1850s women ministers were unheard of.

By 1920 there were 88 ordained Universalist women.

Today over 50% of the ministers in fellowship with the Unitarian

Universalist Association are women.

Heroes- Olympia Brown and Phoebe Ann Hanaford

but not always.

For

years their contributions were ignored.

Prominent

histories of our movement failed to even mention them. For awhile Hanafords

grave was even unmarked.

After

their deaths, these women sunk into obscurity.

It is only in the last 25 or so years that their contributions have been

rediscovered and their stories of courage in the face of adversity retold.

What message does this bring to us today?

I think there are at least three:

1.

There are

trailblazers working today, heroes if you will,

that we are not even aware of. They labor often in obscurity,

spreading a message that is often unpopular or, at best, accepted in a lukewarm

fashion.

The sacrifices these

people make are many. They dont have the best jobs with the highest notoriety

and reputation.

The heroes of

tomorrow are likely obscured from our vision.

2.

If

we are lucky enough to know of one of tomorrows heroes, we are likely not to

greet that person warmly.

Brown and

Hanafords messages were met with opposition or indifference most everywhere

they went. Heroes tend to operate on the fringes of a movement. Neither Brown

nor Hanaford ever had a big church or were perceived as highly successful

ministers.

Only today do we

appreciate what they contributed to our liberal religious movement.

3.

What is

the common accepted wisdom of today may not seem quite so wise in the light of

history.

We see that truth time and

time again in

the lives of Hanaford

and Brown.

That should bring to us

a certain sense of humility.

Are we

open to new, fresh ideas or are we stuck in our old, comfortable thought

patterns?

Do we welcome honest

difference, or do we pay lip service to our claims of tolerance and diversity?

Would

we have welcomed Brown and Hanaford into our homes?

Into our church?

Maybe

maybe

not.

Todays heroes are out there

somewhere. New ideas, new causes, new

solutions to age old problems, new ways of looking at old practices and

traditions.

Lets let our

Universalist women heroes remind us to be as accepting as we can.

The next Olympia Brown may be on our midst, and we dont even see her.

Rational e for UU Ministry

A

sermon by Rev. Don Reidell

Pullman Memorial

Universalist Church Albion, NY

Sunday, March 17,

2002

My conviction to become a Unitarian Universalist minister did not come

from any revelatory "call", but rather arose from a rational and

deliberate consciousness that made me resolve that it is in the office of the

ministry-specifically the Unitarian Universalist ministry-that I could best take

up direct service for humanity.

But

before one ministers to others, he must have a strong belief and faith, and he

must verify to himself the solidarity of that faith, for I believe that

theological integrity plays a major role in bringing wholeness to a minister.

It must be real and organic to him first before he assists

others in developing their own spiritual convictions.

I have sought and I have found that faith in Unitarian Universalism, and

I have an invincible belief in its goodness.

Therefore, in order to best present any promptings and reasons for

wanting to become a Unitarian Universalist minister, and why I am a UU, and to

grant as much clarity as possible for my conviction, I shall first declare my

religious credo, followed by a delineation of the various functions and roles of

the way of life of the Unitarian Universalist minister.

For it is through my faith and my understanding and knowledge of the

various ministerial duties that compelled my decision to enter the ministry.

As every life is born from another life, so also is every freedom born

from another freedom.

Similarly, I maintain, in the domain of beliefs, every faith

is born from a previous faith.

As

Unitarian Universalism emerged out of the Protestant Reformation and the

Enlightenment, my avowal to Unitarian Universalism sprang out of my foundations

in the Lutheran tradition as I began to assert my belief in the free use of

reason and ethics to reinterpret my faith, and as I began to assert my belief in

the vitality of active and fearless thought. I believed that one should worship

God in spirit and in truth, and the form is as inconsequential as the language

we use to worship God in.

The forms

are only means. They are valuable or valueless only as they lead to the goals,

which are the love of truth, the spirit of Jesus, and the service of mankind.

Therefore, I began my search for a liberal approach which would allow a

bedrock on which to construct a meaningful faith for me, built from my own

being, experience, and character.

It

was at this time that I found Unitarian Universalism.

For me this faith is marked by spiritual freedom, by the use of the

rational mind, by faith in the dignity of all men, by the continuance of man's

potentiality, by the spirit of Jesus, by the universal truths taught by all

religions and exemplified in the Judeo-Christian heritage, and by the desire to

serve.

These characteristics flow together in Unitarian Universalism and

reinforce the propensities within us for goodness and human decency.

It means an experience of religion which is the constant seeking for

values which each person continually develops as he creates for himself a

religious way of life through the development of character and conduct.

Therefore, Unitarian Universalism means to me the granting of freedom to

pursue a religion of my own.

There

is no finality in the religious quest for those who have reason,

free-mindedness, and inquisitiveness.

Unitarian

Universalism gives me the inspiration, the fellowship, and the society to

continue my experiments with truth; and it grants me that inward receptivity to

new investigations essential to these experiments.

I do not see my faith as a rival of any other established faith.

Rather, I see them alike in that they are all expressions of man's

religious consciousness.

However, I see in Unitarian Universalism the freedom for

inquiry, for exploration, for hope, for expectations.

It is my hope that my religious credo continues to evolve, to merge with

the current of change in my personal history, as my reason is illumined by faith

and my faith by reason. Unitarian Universalism continues to give me the freedom

for this.

It is this faith that has

given me the revelation and the conviction that the simple doctrine of the

essential worth of man, however humble he may be, may prove to be our greatest

liberating force.

These tenets of

Unitarian Universalism, along with those of the exciting traditions of the free

pulpit, the free pew, and congregational polity, were the initial prompters for

me to wish to become a UU minister. That was 29 years ago. Once I made that

decision, I wanted to know as much as I could about the operations and

organizations of the church; but, above all, I wanted to know the people.

I have had opportunities to plan worship services and preach, both in my

own church and in surrounding UU churches and fellowships.

Each and all of these experiences over the years have increased my

certainty and deepened my compulsion of the UU ministry so that I may work with

people and help them by assisting them in affirming life and by awakening in

them a consciousness of their own spiritual nature and destiny.

This then, in brief, presents the foundation of my Unitarian Universalist

faith, a faith which will perpetually develop and emerge and continually imbues

me with the desire to serve.

I wished to become a UU minister because I believe that the finest worth

in life is that I could do my best in the work I have to do in the world.

It was my desire to put my faith to work, for I know that it involves my

living schedule as well as my mind and heart.

I have taken a position affirmatively about life; I wished now to proceed

to act upon my affirmations by doing my part in the exacting task of making the

ideal of togetherness work, and in doing so to deepen my own wells of

inspiration.

I wanted to associate

myself actively with people, unequivocally asserting that I am responsible for

the present and the future in the world of humanity, that if I do not play my

part beyond the role of self-interest and survival there will be no better

world. I desired to assist in making my religion continue to come of age, for it

is the force of religion which makes people desire the good and which moves the

will to achieve it. I wished to become a UU minister because my faith ties my

life together into a meaning that will absorb all my energies and hopes.

I believed that would make me a part of that process of nature that

unites my own inner spirit with that of my neighbors.

I am aware that the UU ministry is no easy position, for it is committed

to the espousal of ideals which very often are in direct conflict with the

dominant interests and prejudices of contemporary society.

Surely we are a world-conscious generation, and we have the means at our

disposal to see and to analyze the brutalities which characterize individual's

larger social relationships and to note the dehumanizing effects of a

civilization which unites people mechanically and isolates them spiritually.

Therefore, it appears inevitable that a compromise be made between the rigor of

the ideal and the necessities of the day.

It is not an easy task to deal realistically with the moral confusion of

our time.

But it is perilous to entertain great moral ideals without

attempting to realize them in life; they must be brought into juxtaposition with

the specific social and moral issues of the day.

I wanted to be a UU minister in order to make concrete my

ideals by agonizing about their validity and practicability in the social issues

which I and others face in our present society.

It is this which gives the ministry reality and potency.

I entered into the UU ministry firmly believing that

only by giving unreservedly to the work of advancing practical goodness can

positive change be effected.

The

type of ministry which I desired, for it offers greater opportunities for both

moral adventure and for social usefulness than any other office, is the parish

ministry.

At the outset of this sermon, I stated that besides having a clear and

unified theological base out of which grew my desire to become a UU minister,

there is also a knowledge and understanding of the ministerial roles and

functions that I have gained from my observations and experiences; and that it

is also because of my cognition and acquaintance with these varied roles that I

wanted to become a minister.

It is

because I have had direct experience both with ministers and with work in the

church that have served as a process of trial and entrance, of getting to know

what the profession involves so far as work, knowledge, and responsibility are

concerned.

I feel that this experience and close observation had removed

any idyllic or romanticized notions of this office from me.

Illusions must be removed and reality forced in order for the ministry to

take on form and purpose and accomplishment.

Rather, one should enter the ministry of the church with the consent of

all his faculties-mind, heart, and conscience.

It is not enough for a person to want to be a minister; that want, that

compulsion, should be tested against some inventory of the person's abilities

and the needs of the church, the denomination, and the society.

Inasmuch as it was by observation and awareness of the varied ministerial

functions that were of import as part of my decision to become a UU minister, it

seems appropriate to present a brief view of how I perceived each role.

Administration is a necessary part of any human institution, and I would

place the administrative task high on the list of useful aspects of the role of

the UU minister.

In smaller congregations, such as Albion's, the Board of

Trustees carries this role. The job of being responsible for a church today

appears to be one of the hardest jobs anyone is called to do.

In my experience, being an administrator takes much patience

and in many ways more time than doing the job myself.

Yet this extra time must be taken because there are religious

values in this task and the one-man show never serves the purpose of the church

as well as the organization under a skillful administrator. Administrative work

puts the minister into close, meaningful contact with many people. The process

of making real decisions and working with committees who work out the decisions

offers a chance to be involved in real dynamics in the all important function of

working with laypeople.

I believe that the minister as administrator must keep in mind certain

propositions which will assist in the operation of the church. First, that each

person can do something. Secondly, each person wants to do something.

He may not know this exactly, but a good deal of criticism and

unhappiness in a church comes from people who are on the outskirts and not

actively engaged in some part of its labor.

Thirdly, each person needs to do something; it gives them a sense of

purpose and meaning. These are the religious values inherent in the

administrative role.

One of the things that impressed me most is that the church as an

institution is not very different from the educational institution with which I

was acquainted, or, for that matter I suspect, any other institution so far as

the procedures and principles of administration are concerned.

Therefore, I see my own administrative experience related to that of the

needs of the church.

I wanted to become a UU Minster because I believe in the art of the

sermon and I wish to preach it.

The

word for this art is simplicity.

Yet

back of the simple speech there has to be a love of words and of language and

long hours of careful preparation.

But

the minister must know the difference between a sermon and an oration, and this

is known only when there is direct personal contact with the congregation.

He must be saturated with the needs of the people, and this comes only by

close association with them.

The social and the personal elements of our religious faith must be

combined in every sermon.

The sermon is an existential event; it is the one great

moment of experience between the preacher and the congregation. There is a

facing of this great moment after hours of preparation, knowing that in about

twenty minutes it is over.

Yet, I

know that in that brief time great issues may be faced and decided which may

influence and change lives.

I continue to be excited by the UU tradition of the free pulpit, which

allows me to preach what is in my heart and mind. Surely, we should speak of

current events, of things relevant. But above all I believe that every sermon

should speak of the deepest spiritual faith that my heart holds. I believe that

the deeper and ultimate values are what people wish to hear discussed.

It is what they need and want today more than ever before. In such a

role, I have desired to touch the lives of the congregation.

I see preaching as commingled with that of teaching.

Both are to supply the spirit of inquiry.

Part of the task of the minister is to be a teacher of the people, for

teaching is an essential part of equipping and sensitizing individuals and

groups both in facing the center of life and meaning and in facing one's

responsibility to the larger community. But teaching is not a one-way

proposition. The minister needs to learn from the people as much as they need to

learn from him.

The art of teaching

is the art of struggling through all kinds of complex propositions in order to

come to a solid conviction upon which a person can stand.

The area of the pastoral ministry that includes counseling and visitation

is of great importance in achieving a balanced ministry.

I wanted to assist in ministering to those terrifying human conditions of

anxiety, despair, fear, and loneliness.

Marital

crises and the problems of youth and age are ever in need of counseling and

psychological skills. The ministry would allow me to touch lives at crisis

points, to assist in binding up the wounds of the sick and injured and

disturbed, to help the dying patient and his family move toward an acceptance of

death as an integral part of the wholeness of life. I believe that if the

minister cannot give these people a solution to their problems and anxieties, he

can surely listen; it is amazing how often this simple function heals and

encourages.

I see the religious education role of the minister as that of a

facilitator, one who is a leader and teacher and learner, one who serves to

leaven religious education for the total church community, not only for the

children, for surely religious education is a life-long process.

This education is not concerned with a particular class of subjects in

which a person may or may not be interested, but rather is an overall response

to life in which every person is inextricably involved.

Religious education is the individual's response to what he has thus far

learned in life and what life further offers to him. Religious education

provides opportunities for further learning, and will help each person clarify

and interpret his/her experience of life. It should be a shared enterprise of

the congregation, and home and church should interact.

The object of religious education is to give persons the unity of truth

where the elements of humankind-the intellectual, the physical, and the

spiritual are brought into harmony.

In closing, there is one more thing to say.

There are millions of Unitarian Universalists in America today, but not

in Unitarian Universalist churches. There are millions of Unitarian

Universalists who do not know that such a church exists. They do not know its

history. They do not know its basis. They do not know its purposes. They do not

know that they themselves are Unitarian Universalists. If a true religion is to

shape the world to peace and freedom, these people should be joined together to

advance its cause.

Religions with worn out creeds cannot do it.

Irreligion cannot do it. Confused and cultic religions cannot do it.

If the strength of a free person's faith is to be the under girding of

the world tomorrow, a world so full of dangers, yet so rich in opportunities,

and if the people of America must rise to take their place within this venture,

then there must be growth, and multitudes of pioneers.

This will come about partly if Unitarian Universalists will preach their

faith, for there are many who are ready to hear it.

But it will come about most surely if Unitarian Universalists are willing

to live their faith--live it into aim and purpose, fearing nothing but the

reproach of conscience--for such a faith lived into actual life would be the

power of God himself--invincible.

It is my prayer that each of you continue to find this church meaningful

to your life.

That this your church here in Albion serves to enrich your

faith.

Amen.

So

What's the Big Deal?

Pullman Memorial Universalist Church Albion, NY

March 10, 2002

One

of the most satisfying parts of my ministry occurs when a new member or friend

of the church says words like this to me: "Oh, I didn't know about

Unitarian Universalism. What a revelation is has been for me! I'm thrilled to

find a new religious home. I've been searching for sometime, and you were here

along."

As

you can imagine such words bring great joy to me. You would be surprised how

often I have heard such thoughts; more often than you might think. But along

with my good feelings from hearing such words, the cynic in me softly mutters to

my consciousness, "So what's the big deal?" Allow me to explain my

cynical side, even if I must apologize for it as well.

I

am a lifelong Unitarian Universalist. "Born and bred" is a phrase I

sometimes hear. I grew up in the greater Boston area where every city and even

most small towns have a Unitarian Universalist Church. Our denomination

headquarters stand next to the Massachusetts State House in Boston. Unitarians

started our most famous educational institution, Harvard. Universalists founded

my alma mater, Tufts University, in a suburb of Boston. I never had a conversion

experience; I never "discovered" Unitarian Universalism, it's always

just been there. While I am happy to hear about other's joy at finding our

religious home, sometimes I wonder, "What's the big deal?"

Ordinarily

I would have kept this little peek into the darker side of my personality out of

sight. However this sermon series, where you have all three of your religious

professionals affiliated with this church speaking on their perspective of our

faith, has forced me to bring the "big deal" question out of the

closet. Are we truly unique? Do we have something special to offer? What makes

us different? What's the big deal?

My

road to answer the "big deal" question has been filled with diversions

and potholes. But now I do believe I understand. Our big deal has many different

aspects, but in the end it boils down to what might be considered the most

elementary of theological questions: how do we know? . Who is the final decision

maker in the religious journey we are all on? Who decides?

Various

religions have various answers.

For

Roman Catholics, the ultimate authority of religious truth rests with the church

headed by the Pope. The church traces its origins back to the words of Jesus

spoke to Peter. Jesus said:

And so I tell you Peter, you are a rock and on this rock I will build my

church, that not even death will be able to overcome it. I will give you the

keys of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Matthew 16:18-19

How's

that for authority? For Roman Catholics their faith is sure- they are part of

Peter's church. Do as the church says and the doors to the kingdom of heaven

will be unlocked. Guess who hold the key?

Unfortunately

the church abused its standing; the Protestant Reformation resulted. Protestants

answered the question of religious authority in a very different way. We must

return to the Scriptures. The Bible is the Word of God; Read it, study it,

accept it. It is the truth! Religious truth resides not in a church, but in a

collection of books. We hear this message today very strongly from Protestant

fundamentalists.

As

Protestantism matured, it naturally splintered. Men and women read and interpret

passages differently. Cultural differences emerge. Should the Sabbath be on

Saturday or Sunday? Should baptism be done an infancy or in early adulthood?

Should church government be a hierarchy or should power rest with local

congregations? Should church members be required to buy a pew? Protestants of

good faith answered these questions differently, each returning to Scripture to

find evidence for their particular opinion. Churches around this historic square

here in Albion emerged as different groups answered these questions differently.

Fragmentation was the obvious result, but the foundation of the assumption of

the Bible as the final authority of truth remained constant.

We

Unitarian Universalists came from this tradition of scriptural examination.

Initially we Universalists were founded based on our interpretation of scripture

in favor of the idea of eventual salvation for all God's creatures. Early

Unitarians started with an examination of scripture to reject the idea of the

Trinity as unbiblical.

But

we have moved beyond.

There's

a funny thing about allowing individuals to examine religious questions for

themselves. Eventually those same individuals arrive at the conclusion that

they, themselves, must make final religious decisions for themselves. An

important shift occurs, just as it occurred in the 19th century of our religious

movement. No longer is any one scripture or church the exclusive font of

understanding. Inspiration comes from many sources. Transcendentalists saw God

and truth in nature. Rationalists insisted that truth lay in rigorous

examination through the filter of common sense. More recently, some members of

our movement have insisted that truth lies within what some would call our inner

flame.

No

longer does a church or a book wield full control. For many questioners like

ourselves, we end up believing that each and every one of us can decide issues

of religious truth for ourselves. From this principle of individual autonomy and

authority, the rest of our religious values and beliefs have emerged.

What

are some of these values and beliefs? You've heard me speak of them before in a

variety of ways, and I'm sure the sermons by our other ministers have covered

them as well. I'll provide only an overview.

We

value human dignity. Earlier Universalists used a phrase in their 1935 Avowal of

Faith that sums this up well: "the supreme worth of every human

personality." We believe no person, government, church or creed has the

right to encumber any individual's search for religious truth and practice of

belief.

We

value individual responsibility. Not only do we have the freedom to make up our

minds, we have the obligation as well. Freedom does not allow us the option of

opting out of seeking meaning and truth. Understanding, both on a personal and a

cultural basis, comes only with continued and ongoing examination and

refinement. We are part of that process.

We

value tolerance. We understand that all the answers are in our basket. We

understand that different cultures, races, and even sexes will, over time, come

to differing conclusions. Rather than be frightened by this diversity, we

welcome it, or at least try our best to remain welcoming. We strive not for

conformity or unanimity, but rather openness and acceptance.

We

value the future. Our faith, while we hope respectful of the past, seeks not

only preserve old words and thoughts, but to encourage new. We are among the few

religious movements who believe, to use the words of Samuel Longfellow, that

"revelation is not sealed." That is Longfellow's way of stating a

simple yet profound principle: "we don't have all the answers." Unlike

other religious faiths reinterpreting old stories or ideas, we humbly

acknowledge that we don't always know where the future will lead us.

We

value "reverence." By reverence I mean an appreciation for all this is

around us- the gift of life itself, the ongoing stream of creation, the power of

love. While we possess the power and responsibility of religious judgment, there

is much that goes on around us that we but vaguely, if at all, understand. We

stand reverent not for what little we know and understand, but the vast spheres

of our world we don't understand. Some of us call that unknown God, others

prefer a different term. Sometimes forget our reverence; we don't stay humble;

sometimes we become puffed up with our own power, but we keep trying.

We

value community. If we are reverent to the world around us, we certainly ought

to be reverent to those in our midst. We UU's are few in number. Our dollars are

stretched. We certainly can, however, show care and concern and we travel the

often bumpy road of everyday living. We honor one another, especially in times

of trouble or times of life's special moments.

A

few years ago this very congregation, with many of the faces present here this

morning, engaged in a unique process. We set out, in a very organized and

structured fashion, to determine what beliefs and values held us together. We

asked ourselves what is the metaphorical glue that binds us. Can you imagine any

other church attempting such a task? I can't.

In

my humble judgment we were successful in our goal beyond my wildest

expectations. We arrived a statement we call our Church Covenant. We read it

together every Sunday that I occupy the pulpit. We do that in part because I am

so impressed with how well we captured ourselves, and how well we were able to

come away from the process living out our goal of tolerance. The words bear

repeating once again, as a summary of who we are:

Enriched by our unique legacy, we come together:

To encourage personal spiritual growth in an open,

democratic environment,

To search for truth and meaning in our lives,

To model together our values of love and respect,

To advocate in a spirit of optimism for freedom and

tolerance in our community.

What's

the big deal? I guess for some of us who are used to this sort of thing, we

don't understand very well the emotions of others who have just discovered us.

But I'll try to summarize what I think other feel.

The

big deal is this: that you can find a religious home where you are empowered to

think for yourself; where you are encouraged to doubt, to ask questions, to

experiment. The big deal is further that there is a religious community,

imperfect at times, which will foster and nourish your questions AND your

answers.

These

homes are hard to find. I dare to say that there is no other community in

Orleans County where such an atmosphere exists. We can be proud; we are

Unitarian Universalists: it's a big deal!

Embedded

in our hymnbook are these closing words by James Villa Webb:

Love is the spirit of this church, and service is its

law.

This is our great covenant:

To dwell together in peace

To seek truth in love,

And to help one another.

Amen

For

as long as I can remember, being a Unitarian has been part of the very

foundation of my identity. That the Dodges were Unitarians was a statement

of fact, one of the ordering principles of my universe - as basic to my sense of

self as the Dodges were Americans, spoke English. What it meant to be a

Unitarian, however - and then a Unitarian Universalist - went unasked and

therefore unexamined for years.

My

first inkling that I didn't really know what being a Unitarian was all about

occurred to me as I was picketing with my Sunday school classmates - including

the minister's family - for a cause I only vaguely understood. As we

walked round and round in front of the offices of the Board of Education,

holding placards about injustices in the City School system, I wondered how I

would explain my participation in the gathering media.

An

imaginary microphone was thrust in my face, and I was asked, "Could you

please tell our listening audience just what are you protesting here

today?" The imaginary journalist continued, "And, if I'm not mistaken,

you are here as a member of your church school. Could you please explain the

connection between your religious affiliation and concerns for public

education.?

I

sputtered and babbled in my imagination. Slogans from our signs and chants

were all I could repeat: something about fighting injustice, fighting for equity

in education." The truth is I didn't really understand either the

educational conflict or the religious connection. But the fear of the

media's potential question forced me to acknowledge that I didn't have a clue

what we were challenging and why it was a matter of religious concern.

Mercifully, the press didn't press me for information, but the sheer terror of

the possibility that I might need publicly to explain my presence and commitment

awakened the need for greater awareness about my religious convictions and

raised questions that I am still answering today.

This

was in the early 1960s. The immediate concern was bussing children in and

out of the Boston City School District. The larger issue, of course, was Civil

Rights. I came of age as a Unitarian Universalist during an era of

heightened social consciousness - an era in which the denomination itself

came into being. Social action - the daily practice of living one's

religious principles, often publicly and politically - was a shaping force

in my early understanding of what it meant to be a Unitarian Universalist. In my

eleven-year old head being a good Unitarian Universalist and being a good

citizen were synonymous.

Paradoxically,

there was another aspect to my religious life, even church life, that developed

simultaneously on a parallel track. Ever since I was a very young child I

had an abiding sense of the sacred, in the natural world, in the arts, and in

language. I was the self-appointed keeper of the animal cemetery, charged

to ensure that due reverence was observed when we buried the cat's more than

occasional quarry. I have always loved music and sang in the church choir

year after year. Stirred by the music, the words, and the joining of voices,

singing was a transporting, transcendent experience. I felt, surely, the

sacred was present at these times. I also felt the presence of mystery in

the "close hand holy darkness," to borrow Dylan Thomas' word,

every night when I went to bed. I don't remember ever learning to pray, but

prayer very early on was a precious part of my life. How keenly I remember

my earnest nightly conversations with God. In my spoken and later written

prayers, I yearned for connection with the ultimate.

A

few moments ago, I introduced this picture of my emerging spiritual life

paradoxically on a parallel track to my developing sense of my Unitarian

Universalist identity. The essence of the paradox is this: my spiritual

life was a private matter, one I nurtured alone. My intellectual and political

identity was unquestionably Unitarian Universalist. My spiritual identity,

however, was unaligned/unaffiliated.

I

couldn't have articulated this internal chasm even a week ago. The internal

truth of it was viscerally familiar to me but I've only just brought it up to

the light through thought and language. Exploring my religious journey once more

through the lens of this morning's sermon, I realized how many unresolved issues

are brewing beneath the surface of my steadfast Unitarian Universalist identity.

In

the fast-forward mode, let me share a few of the ways these issues have played

out in my life. The story told so far takes me to about age 17 -

formative years, for sure. The next 20+ years, I must count myself among the

great unchurched. Give me a form to fill out asking for my denomination - ask me

point blank about my religious affiliation - and I would have answered

immediately Unitarian Universalist - but the church wasn't a part of my daily

life. In fact, I began visiting other churches. There was a stint visiting

the Presbyterian church, a brief time among the Religious Society of Friends, a

visit here and there to a UU fellowship, and soon after we moved to Rochester

- sometime in the late '70's-early '80's - a Sunday spent at First Unitarian on Winton Road.

I was literally aching for community, but nothing fit. There was too much talk

of God and Jesus in certain settings - I found I couldn't participate fully

in the "repeat after me" sections of the service - and too little

sense of the sacred in others. The ardent call to boycott grapes from a UU

pulpit felt as prescriptive as the sermons from other churches.

I

was on an urgent quest but I couldn't tell you what I was looking for.

And

then one day, I found it. My children were growing up without a faith community

and that finally galvanized me into action. They'd been periodically dressed up

and dragged to church school over the years so they weren't totally surprised

when their mother went into high gear one Sunday morning. With them safely

installed in a class, I slipped into the back of the Winton Road sanctuary.

I can't tell you what the sermon topic was, which hymns we sang - all I

knew is that I'd found a part of me that had been missing for ages. I came

totally unprepared for the tears that were released that day.

Why

then? What was so different? What had been missing before? Had the denomination

changed somehow in the intervening years?

There

are, I believe, both denominational and personal answers to these questions

- and they are intricately interwoven. The denominational passage of the

Purposes and Principles in the mid-1980s was a critical articulation of the

forces that bound Unitarian Universalists together. To be a liberal religious

community does not mean that anything goes. Contrary to some outsider's views

liberal and lazy are not interchangeable. Ours is an arduous way.

Practitioners in many other traditions focus on an established canon - the

Bible, a theology - and test their beings against it. What would Jesus do? What

does the Bible demand? UUs do not have a single starting point. In

religious parlance, we might say that our canon is not closed. Revelation does

not belong to the past alone but is an every present reality.

Sitting

in the sanctuary that day, I didn't know all that had transpired in the

denomination; I just knew that something deep within me had been touched

and opened. As much as the denomination may have evolved over the

years, I believe that essential changes have been at work within me. My

connections with the sacred had continued privately. I had never ceased my

nocturnal - and then some - dialogues with God. My sense of the holy in the

natural world had grown in the intervening decades, and I had a growing

"reverence for the reverence of others." What changed was my

acknowledgement of the need for and gift of community. We are both solitary and

social creatures, spiritual and political animals.

I

was born a Unitarian, and for years took it as a given - like my name,

nationality, eye color. I only truly became a Unitarian Universalist, however,

years later when I chose the denomination, acknowledging that I cannot be fully

human on my own.

"Take

courage, friends. / The way is often hard, the path is never clear, / and the

stakes are very high. Take courage. / For deep down, there is another truth: you

are not alone."

Wayne A. Arnason, Singing The Living Tradition, #698

Amen.

Continuing

Revelation

Rev.

Donald Reidell

Theme: Modesty is

the ingredient for on-going revelation.

1. The clergy,

especially, must have humility.

2. Religious

liberalism depends on the principle that revelation is continuous.

Ultimate meaning has not been captured.

3. Service is a

parallel to this concept.

Charles Hartshorne

drew a circle - The empty space was the given knowledge of science. Ten dots

were then added around its circumference, representing the new questions of

science. The larger circle was drawn around the first, assuming successful

answers to the questions, and on that placed 20 dots. Etc.

In other words, the

more science knows, the more it wants to know.

But this is not he

model of orthodox religions. They claim absolute truth!! All of them believe in

a single revelation:

a. Hindu tradition

claims the eternal truth in the Vedas.

b. Hebrews have a

special privilege of being born Jews.

c. Buddhists have

the Dharma.

d. Islam has

Mohammed as the seal of the prophets, and the Koran as the highest

authority.

e. Christians have

Jesus Christ as God in human form and as Redeemer.

Each religion

assumes superiority. And they all breed tribalism and suspicion.

When revelation is

frozen, the mind is frozen as well.

4. No one has all

the answers.

5. Courage is

required to continue to search, and to resist the temptation of finality.

6. The mood and the

core of liberal religion is to strive to find new answers. To continue to doubt

and to challenge.

7. Yet the search is

a refinement of understanding. The God of Abraham was not the God of Jesus, and

the God of Paul is not the God of the 21st Century.

8. And it is the

same in our personal lives. We need not apply revelation only to religion. Who

would close the book on their own development as we move through life?

9. It is a joy to

discover. Our minds are ever expanding if revelation is not sealed.

Sermon Summary, December 8, 2002

Its

hard to believe we have a masterpiece in our midst.

I am referring, of course, to our Tiffany windows,

especially the window in our west transept, which is considered the most

significant of the group, showing Christ with his hands outstretched toward us,

as if giving us consolation.

In

addition to its fine craftsmanship, this window was signed by Tiffany

most

unusual.

I

must confess I never thought much about this window; in fact I have consciously

ignored it for many years. It is only from recent Sundays when I have sat in a

pew that I have begun to appreciate the masterpiece in our midst.

This

beautiful window depicting Christ wearing a crown of thorns and a glow emanating

from the top of his head is a good representation of the state of Universalism

in the 1890s.

We were then a

solely Christian movement, which emphasized a God so loving that He would, in

the end, return all his creatures to the joyful bliss of heaven.

Jesus was His Messenger, the Bearer of the Good News of Gods

redemption to all.

Our

beliefs have grown and changed in the past 100 years, as you well know.

No longer does the window seem to represent who we are as a worshipping

community. In fact, for many the window has come to represent the orthodoxy we

have rejected.

Some of us, myself

included, have been uncomfortable with the window.

We prefer to pretend sometimes that its not even there.

My

personal attitude has changed in the past few weeks as I have had time to

contemplate the window from a perspective other than in the pulpit.

The window has messages and meanings still vital to our liberal religious

movement here in Albion.

First

is certainly the whole idea of gift giving for future generations. Try for a

moment to get inside George Pullmans head. He knew certainly that the church

was going to outlast all those who he knew who came to the dedication. He

understood that this building and that this church as an organization would be

here long after the organized cast of characters had perished. He really did, I

think, have US in mind, you and I! Not other people, just this small band of

people of who we are.

We

have been given this great treasure, just a few of us! I think he knew that the

church would live for centuries. He knew back then that there would be men and

women long after his death that occupied this room for worship and that looked

at this window for inspiration. He was giving for many, many generations. We are

todays recipients. Its almost hard to comprehend the magnitude of that

gift. Given to a very few people. Us!

What

gifts are we giving? Oh, I dont think we are going to be in the situation of

calling up Louis Tiffany having him bring up another window.

We dont own a railroad car company. Yet when we look at the gift that

has been given to us, the inevitable question comes up: what gifts are we

giving- not just to the people around us, not just to the faces that are

familiar, but to the future generations? Just as George Pullman gave us an

artistic masterpiece, what are we doing within our means for people not yet

born? This window forces each of us to ask questions about own gifts to

posterity. Will we leave the world a better place?

This window reminds us that the yardstick by which we will be

measured are not the gifts we give one another around this time of year, but by

the gifts to generations yet unborn.

There

is another message, I believe.

We

dont use the verb console much.

Somehow

its gone out of style. We console, perhaps, only at the time of death.

Jesus in our window reminds us of the power of the simply act of

consolation, not just at the end of ones life, but throughout it. It is so

easy yet so powerful to let another know that you care about their burdens, that

you have genuine concerns about the troubles they bear. We can reach out in

simple way and console one another. It is truly a gift we can share with each

other.

So

may we look at our 10 foot Jesus with a new vision. Hes been standing in the

window looking down at us in this room for since 1895, a span that includes

three separate centuries.

What

narrow dogma concerns we have about the window seem to fade in the perspective

of history. The window can still speak to us, if we will but listen.

There is a message of caring, of consoling, and of concern for the

future. Those messages are in fact part of our liberal Unitarian Universalist

faith today and I assume will be in the future.

We

have been entrusted with an object of great beauty, and the lessons of that

object still ring true over a century after its creation. We can but say,

Thank you, George Pullman.

Sermon

on Blaise Pascal

Nov. 17, 2002

What

a shimmer then is man; what a novelty, what a monster, what a chaos, what a

contradiction, what a prodigy. Judge of all things, imbecile, worm of the earth,

depository of truth, a sink of uncertainty and error, the pride and refuse of

the universe.

(

just

in case we think highly of ourselves.)

Blaise

Pascal was a highly prominent French scientist. Acutely religious and trained to

be a keen observer, he then turned to theological musings. In 1660, he wrote the

following reflection on the human condition, though I should caution it is a

hard and realistic portrait.

Our senses perceive no extreme. Too much sound deafens us. Too much light

dazzles us. Too great distance or proximity hinders our view. Too great length

and too great brevity of discourse tend to obscurity. Too much truth is

paralyzing.

First principles are

too self evident for us. Too much pleasure disagrees with us.

Too many concords are annoying in music.

Too many benefits irritate us.

We

wish to have the wherewithal to overpay our debts. Extreme youth and extreme age

hinder the mind, as also too much and too little education.

In short, extremes are for us as though they were not and we are not

within their notice. They escape us or we them. This is our true state. This is

what makes us incapable of certain knowledge and of absolute ignorance. We sail

within a vast sphere ever drifting in uncertainty, driven form end to end. When

we think to attach ourselves to any point and to fasten to it, it waivers and it

leaves us and if we follow it, it eludes our grasp, slips past us and vanishes

forever. Nothing stays for us.

This

is our natural condition.

And yet

most contrary to our inclination, we burn with desire to find solid ground and

an ultimate sure foundation where on to build a tower reaching to the infinite.

But our whole groundwork cracks and the earth opens to abysses. Let us

therefore not look for certainty and stability. Our reason is always deceived by

fickle shadows.

Nothing can fix the

finite between the two infinities, which both enclose and fly from us.

-Blaise Pascal

Everyday

I, like you I am sure, am influenced by ideas and beliefs and actions and

touched by various forces and objects and conditions; possessed by various hopes

and dreams and emotions which I really have to interpret and keep on

interpreting in order to exist.

Sometimes

I am skeptical or convinced, cynical or trusting, optimistic or pessimistic,

rational or incoherent as I often shift through those moods to cope with the

realities of the world.

Occasionally,

however, I fall into a mood, which pervades everything.

It is very heavy, complex, significant and at bottom it involves a

serious question which I ponder intensely until I feel almost as if I should

give up on it.

What

is real?

What

is real, not ideal, not alleged, not imaginary, not artificial, not irrational,

not self-serving, but what is real?

Such

a question is itself extremely unnerving because it disrupts our defense

mechanisms and it challenges our artful fictions and it threatens to sow

disillusionment. Thomas Stearn Elliot observed, We cannot bear to much

reality.

Nonetheless, I know a

figure whose entire life was engulfed by the search for reality.

Totally devoted to perceiving existence in its essence, to fully

understanding things as they really are, to painfully describing the actual

nature of the world with no need to deny, no need to dodge or to rig the

evidence in some kind of favorable direction but always pursuing the literal

truth and permanently caught in the realistic mood; Blaise Pascal was born in

Clermont, France in 1623.

A sickly,

precocious child, he was educated entirely by his father at home.

At the age of eleven, he accurately applied the first twenty-three

propositions of Euclid and only five years later he published a paper on

geometry, which shook completely the mathematical world. By the age of

twenty-six, Pascal was the leading scientist in Europe. And, along with his

theories in calculus and acoustics, he devised a barometer, a hydraulic press,

and a calculating machine, as well as a bus plan for traffic across greater

Paris.

Never marrying, he died in

his thirty-ninth year in 1662.

Pascal was a very rare combination.

He was a scientist with an unerring objectivity.

He was a fanatic for precision, but he was also a person of deep feeling,

with a profound sensitivity to human suffering.

He was a mathematician, a highly respected expert in the field of

abstract numbers, but he was also a poet, with a very vivid style, one who